When I first started designing strength programs, I struggled with one crucial element: how to accurately quantify training intensity without relying solely on percentages of one-rep maximums. Enter RPE – Rate of Perceived Exertion – a game-changing method that revolutionized my approach to programming! In today’s fitness landscape, understanding and implementing RPE has become essential for coaches and athletes seeking optimal results.

I still remember the frustration of watching a client struggle through a workout that looked perfect on paper – 85% of their tested max should have been challenging but manageable. Yet there they were, grinding through reps that clearly exceeded their capacity that day. Was their max testing off? Were they not recovered? Had I miscalculated?

Did you know that studies show RPE-based training can lead to better adherence and potentially superior strength outcomes compared to percentage-based methods alone? I certainly didn’t when I first started coaching! Research from the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that autoregulated training using RPE produced greater strength gains in the squat compared to traditional percentage-based methods over a 6-week period.

Whether you’re a coach designing programs for clients or an athlete managing your own training, mastering RPE will transform your approach to strength development in 2025 and beyond. Trust me, I’ve seen this method work wonders with athletes ranging from absolute beginners to elite powerlifters competing at the national level.

What is RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) in Strength Training?

RPE, or Rate of Perceived Exertion, is basically your subjective rating of how hard an exercise feels. I know, that sounds super simple, but there’s actually a lot of science behind this concept!

The RPE scale used in strength training today isn’t actually the original version. Back in the 1960s, a Swedish psychologist named Gunnar Borg developed the first RPE scale that went from 6-20 (weird range, right?). It was mainly used for cardiovascular exercise. Over the years, strength coaches modified this concept, and powerlifter Mike Tuchscherer popularized what most of us now use – a 1-10 scale specifically for resistance training.

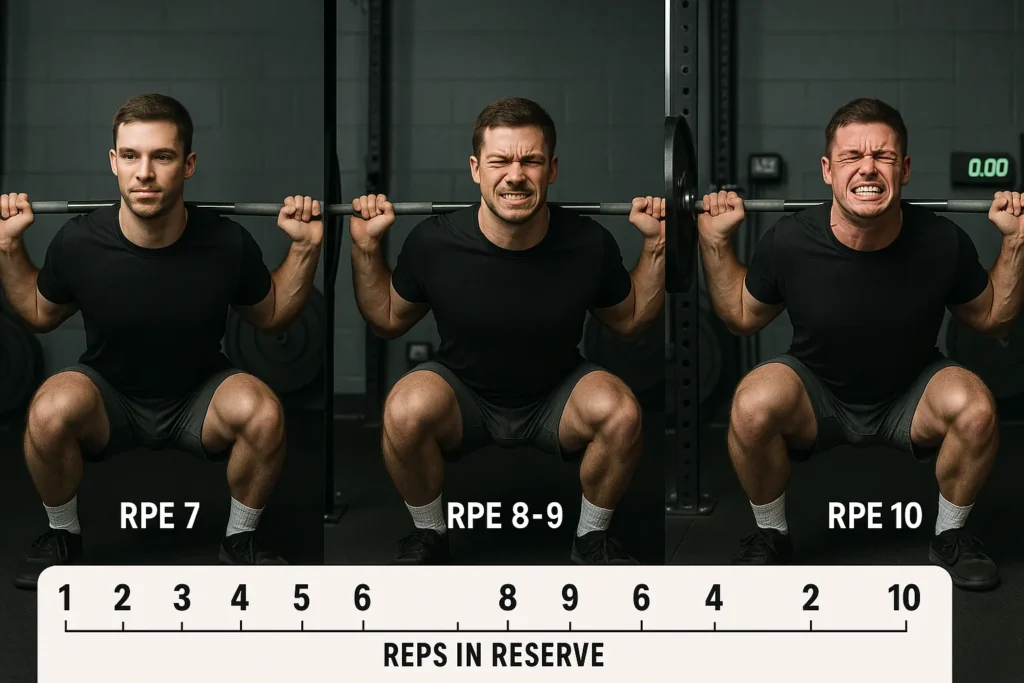

I remember being totally confused about the difference between RPE and RIR (Reps in Reserve) when I first encountered these terms. They’re related but not identical! An RPE of 8 typically means you could do 2 more reps before reaching failure, so that’s 2 reps in reserve. But RPE is more holistic – it considers not just proximity to failure but also the overall difficulty, including factors like speed and technique breakdown.

The psychological aspect of RPE is something I underestimated at first. Your perception of effort isn’t just physical – it’s influenced by mood, environment, expectations, and even social factors. I’ve had training sessions that felt like RPE 9 when I was alone in my garage gym but magically transformed to RPE 7 when training with motivated partners. The mind-body connection is fascinating!

One of the biggest misconceptions I encounter when teaching RPE to new clients is that it’s too subjective to be useful. “How can I program based on feelings?” they ask. But here’s the thing – with practice, most lifters become remarkably accurate at gauging their RPE, often within a half-point of objective measures! I’ve tested this repeatedly with velocity tracking devices that can estimate proximity to failure, and experienced lifters are surprisingly precise.

Another myth is that RPE is only useful for advanced lifters. That’s total nonsense! In fact, beginners often benefit most from RPE because their maximal strength is changing so rapidly that percentage-based approaches quickly become outdated. I’ve used RPE successfully with complete novices by simplifying the concept – “Leave 3-4 reps in the tank” is much more effective than “Lift 67.5% of your one-rep max.”

Benefits of Using RPE for Strength Program Design

Switching to RPE-based programming was a total game-changer for both my training and my clients’. The biggest benefit? Auto-regulation. That fancy word just means your training adapts automatically to how you’re feeling and performing on any given day.

I’ll never forget coaching a national-level powerlifter who was supposed to hit squats at 87% for sets of 3. On paper, that was 405 pounds. But he’d just returned from an international flight and was clearly struggling. With percentage-based training, we’d have been stuck. With RPE, we simply adjusted – “Hit sets of 3 at RPE 8” – which ended up being 375 that day. The following week, when he was recovered, RPE 8 was actually 415! Same stimulus, different loads based on daily readiness.

The recovery benefit is huge too. I used to run myself into the ground following rigid percentage-based programs that didn’t account for my crazy work schedule or lack of sleep. RPE training taught me to respect recovery without sacrificing intensity. On good days, I push harder. On rough days, I back off but still train with purpose. My progress has been more consistent as a result, and I’ve had way fewer injuries.

The research backing RPE is pretty convincing. A 2018 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that subjects using autoregulatory training (including RPE) improved their bench press 1RM by 17.5kg on average, compared to 7.6kg in the group following percentage-based training. Those numbers aren’t small potatoes!

One benefit I didn’t expect was the psychological advantage. With percentage-based training, there’s often anxiety about hitting prescribed numbers. “Today I MUST squat 315 for 5 sets of 3” creates pressure. With RPE, the goal becomes “Today I’ll squat 5 sets of 3 at RPE 8” – which puts the focus on the effort rather than the absolute weight. I’ve noticed this reduces performance anxiety and actually leads to better sessions.

Long-term, RPE training has proven more sustainable for nearly everyone I work with. Instead of programmed peaks and valleys, there’s a more consistent approach to intensity that accounts for the natural ebbs and flows of human performance. My clients stay more consistent, miss fewer sessions, and report greater satisfaction with their training. That’s a win in my book!

How to Accurately Assess Your RPE

Learning to accurately assess your RPE is sorta like learning to taste wine – at first, everything’s either “easy” or “hard,” but with practice, you develop a much more nuanced palate! I spent months refining my ability to distinguish between an RPE 8 and RPE 9, and it was worth every bit of that effort.

The physical signals are your best friends when learning RPE. For me, RPE 6-7 is characterized by smooth, controlled reps with minimal slow-down. An RPE 8 typically shows a slight grind or deceleration on the final rep. RPE 9 involves significant slowing on the last rep, maybe some form breakdown, and definitely some serious effort faces! And RPE 10? That’s complete failure – you couldn’t do another rep if someone offered you a million bucks.

I made every possible mistake when learning RPE assessment. The biggest was underestimating my RPE on compound movements – I’d call a brutal squat set an “RPE 8” when it was clearly a 9.5. My coach caught this by filming my sets and showing me the bar speed. The video doesn’t lie! Another common error is overestimating RPE on isolation exercises – that bicep curl might feel like death, but if you’re honest, you could probably squeeze out 3 more reps.

Recording your training is the single best way to improve RPE accuracy. I spent six months filming all my working sets and reviewing them immediately after. I’d guess the RPE before watching, then revise my assessment after seeing the video. This feedback loop rapidly improved my perceptual accuracy.

A training log with detailed RPE notes becomes invaluable over time. I note not just the RPE but also subjective feelings: “Felt like RPE 8.5, bar speed slowed significantly on last rep, slight form breakdown.” These detailed notes help you identify patterns and refine your perception.

External validation helps tremendously. I regularly ask training partners for their assessment of my RPE based on what they observed. Sometimes they see things I don’t feel! This external feedback helps calibrate your internal perception. Just yesterday, my training partner called my bench press set an RPE 9 when I thought it was an 8 – rewatching the video, he was right!

Finally, connecting RPE to concrete outcomes improves accuracy. If you hit 5 reps at what you called RPE 8 (meaning you should have 2 reps in reserve), try occasionally doing an AMRAP set to confirm. Could you actually get 7 reps? If not, you’re underestimating your RPE. This occasional testing keeps you honest and improves your perceptual accuracy over time.

Implementing RPE in Your Strength Program

Converting from percentage-based programs to RPE guidelines can be tricky at first. I remember feeling totally lost when I made the switch! A good rule of thumb I’ve developed: 70-75% typically feels around RPE 6-7 for most lifters on compound movements, 80-85% usually correlates to RPE 8, and 90%+ generally feels like RPE 9 or higher. But these are just starting points – your mileage may vary depending on your leverages, experience, and how you’re feeling that day.

When designing RPE-based programs, I like to create “intensity zones” rather than fixed percentages. For example, during a hypertrophy block, I might program “3 sets of 8 @RPE 7-8” for main movements. This gives the lifter flexibility within a productive range. During strength phases, I might tighten this up to “4 sets of 3 @RPE 8” to ensure sufficient intensity while preventing grinding reps that can lead to breakdown.

I made a huge mistake when first implementing RPE by using the same scale for all exercises. Big compound lifts like squats and deadlifts simply feel harder than isolation movements! These days, I calibrate expectations: an RPE 8 deadlift is genuinely challenging, while an RPE 8 lateral raise might still feel relatively comfortable. The RPE scale needs exercise-specific calibration.

For beginners, I’ve found it helpful to start with wider RPE ranges and more submax work. “3 sets of 5 @RPE 6-7” gives new lifters room to practice the movement while developing RPE sensitivity. As they advance, we gradually narrow the ranges and increase the average intensity. By the intermediate stage, most lifters can handle more precise prescriptions like “4 sets of 3 @RPE 8.5.”

Weekly undulation using RPE has been incredible for sustainable progress. Instead of the old “light day, medium day, heavy day” approach with fixed percentages, I now program based on RPE targets: “Monday: 3×5 @RPE 7, Wednesday: 3×5 @RPE 8, Friday: 3×3 @RPE 9.” This creates natural variation while ensuring appropriate stimulus at each session.

Balancing RPE with other programming variables took me years to figure out. Volume and RPE have an inverse relationship – higher RPE work typically requires reduced volume to manage fatigue. For strength blocks, I might program fewer total sets (3-4) at higher RPE (8-9), while hypertrophy blocks might include more sets (4-6) at moderate RPE (7-8). Finding this balance is more art than science, but it’s critical for program success.

Using RPE for Different Strength Goals

Let me tell you, adapting RPE for different strength disciplines was a game-changer in my coaching practice! Each strength sport has its own unique demands and recovery patterns that make RPE implementation slightly different.

For powerlifting, I’ve found that a more conservative RPE approach works wonders during meet preparation. I remember coaching a 74kg lifter who was notorious for pushing too hard and burning out before competitions. We implemented a strict “no sets above RPE 9 within 3 weeks of competition” rule, and suddenly his platform performance skyrocketed! For powerlifters, I typically reserve RPE 9-10 work for specific test days, using RPE 7-8.5 for most training to balance intensity with recoverability.

Olympic weightlifting requires a different RPE approach entirely. The technical demands and neural fatigue from these lifts mean that RPE scales differently! What feels like an RPE 7 technically might be an RPE 9 from a strength perspective. I learned this lesson the hard way when programming for a weightlifter who kept pushing technical RPE too high and saw his performance decrease. We adjusted to use separate RPE ratings for technical execution and perceived effort, which solved the problem beautifully.

When it comes to bodybuilding, RPE takes on yet another character. I’ve found that most bodybuilders benefit from higher-volume work at moderate RPE (7-8) rather than grinding near-maximal sets. The exception? Intensification techniques like drop sets, where pushing past normal RPE limits makes sense. One approach I’ve had success with is “RPE ramp-ups” – starting a movement at RPE 7 and increasing by 0.5 each set until reaching RPE 9 on the final set.

For athletic performance, RPE becomes even more crucial due to the need to balance sport practice with strength training. I’ve worked with several college athletes who had wildly varying recovery capacity based on their practice schedule. Using RPE allowed us to maintain training intensity on good days while backing off appropriately when practice had been particularly demanding. Generally, I keep athletes in the RPE 7-8 range for main lifts, rarely pushing beyond that except during off-season periods.

Recovery-focused training with RPE has been a revelation for managing overreached athletes. I once had a client come to me after following a brutally high-volume program that had left him completely fried. We implemented what I call “RPE caps” – no training above RPE 8 for four weeks, with most work in the 6-7 range. This allowed continued training stimulus while prioritizing recovery, and his performance rebounded dramatically within a month.

In rehabilitation settings, RPE serves an entirely different purpose. When returning from a pec tear, my own training utilized a conservative “RPE ceiling” approach. We started with nothing above RPE 6 on pressing movements, gradually increasing the ceiling by 0.5 every two weeks. This methodical progression kept me honest about intensity and prevented re-injury that might have occurred with percentage-based loading.

Combining RPE with Objective Measures

Integrating RPE with objective metrics took my coaching to another level! There’s something powerful about combining the subjective “feel” of a lift with hard data that quantifies performance.

Velocity-based training (VBT) has the strongest correlation with RPE in my experience. I invested in a GymAware unit a few years back and discovered fascinating patterns. For most of my intermediate lifters, an RPE 7 squat consistently moves at about 0.5-0.6 m/s, while RPE 9 drops to around 0.3 m/s. This relationship isn’t perfect – sometimes a technically poor rep feels harder (higher RPE) even with decent velocity – but the correlation is strong enough to be useful.

I had a funny experience when first using VBT with clients. One particularly stubborn powerlifter insisted every set was “RPE 8” despite clear technical breakdown and slow bar speed. When I showed him the velocity data indicating he was closer to RPE 9.5, he was shocked! The objective feedback helped him recalibrate his perception, and his training immediately became more productive with more accurate self-assessment.

Heart rate variability (HRV) monitoring has become another valuable tool in my RPE implementation toolkit. I noticed that on days with significantly depressed HRV (indicating higher physiological stress), RPE tends to be elevated for any given workload. Now I use morning HRV readings to help guide RPE expectations – if HRV is down 20% from baseline, we might adjust RPE targets down slightly to account for the higher perceived difficulty. This simple adjustment has made programming much more personalized.

Force plate measurements opened my eyes to the relationship between mechanical output and perceived effort. Using a force plate with several advanced lifters, I discovered that peak force production often remains relatively stable even as RPE increases from 7 to 9. What changes is usually rate of force development and power output. This taught me that RPE isn’t just about strength – it’s about how efficiently you can express that strength on a given day.

Creating a comprehensive feedback system takes time but pays massive dividends. My current approach combines daily readiness metrics (HRV, subjective wellbeing scores), performance metrics during warm-ups (bar speed on standardized loads), and RPE ratings for working sets. This three-tiered system provides a complete picture of training status and helps make programming decisions much more precise.

One word of caution from my experience: don’t let objective metrics override RPE completely. There have been sessions where all the technology indicated I should be performing well, but my RPE was through the roof. In those cases, respecting the subjective feedback has always been the right call. The body sometimes knows things that technology can’t measure!

Common RPE Programming Mistakes to Avoid

Boy, have I made some epic RPE programming blunders over the years! The biggest was definitely overestimating recovery capabilities – both my own and my clients’. When I first discovered RPE, I got excited about the potential for pushing harder on good days. What I didn’t account for was the cumulative fatigue from consistently training at high RPE. I remember programming 3 weeks of squats at RPE 8-9, only to crash spectacularly in week 4!

These days, I’m much more strategic with RPE distribution. Most training hovers around RPE 7-8, with targeted exposures to RPE 9 during strength-focused phases. I’ve found that most lifters can handle about 2-3 truly hard (RPE 9+) sets per movement per week without compromising recovery. Anything beyond that requires very careful management of volume and frequency.

Inconsistent application between exercises is another common mistake I’ve both made and observed. I once programmed deadlifts and squats with identical RPE schemes (5×3 @RPE 8) in the same week, not accounting for the vastly different recovery demands. The result? A zombie-like client who could barely function by Friday! Different movements can handle different RPE exposures – deadlifts typically need lower average RPE than bench press for sustainable progression.

Movement pattern specificity for RPE was something I learned the hard way. RPE 8 on a squat feels very different from RPE 8 on a bicep curl! This seems obvious now, but I initially treated RPE as universal across all exercises. I’ve since developed more nuanced guidelines: compound barbell lifts might progress from RPE 7 to 8.5 over a training block, while isolation movements might work in the RPE 6-8 range for higher volumes without ever touching RPE 9.

Fatigue accumulation is the silent killer of good RPE-based programs. In my early days of using RPE, I’d program multiple RPE 8-9 sessions back-to-back, not accounting for the residual fatigue. Now I’m careful to include explicit deload periods – either as full deload weeks with reduced RPE (nothing above 7) or as daily undulations where RPE varies throughout the week to allow for recovery.

Psychological factors affecting RPE accuracy caught me by surprise too. I noticed that competitive lifters often underreport RPE during preparation phases due to ego – nobody wants to admit they’re struggling with weights they “should” handle easily. Conversely, some lifters consistently overreport RPE during deload phases, perhaps to justify feeling tired. Building awareness of these psychological tendencies has made me a better coach and more accurate with my own RPE ratings.

The biggest program design error I see is failing to periodize RPE itself. Just as volume and intensity should fluctuate over a training cycle, so should RPE exposure. A well-designed RPE progression might start a block with sets at RPE 6-7, gradually increase to RPE 8-9 during the intensification phase, then deliberately drop back to RPE 6-7 during a deload. This planned variation in perceived effort is crucial for sustainable progress.

RPE for Special Populations

Working with diverse populations taught me that RPE isn’t one-size-fits-all – it needs to be adapted for different groups! Masters athletes (40+ years) have been particularly interesting to work with from an RPE perspective.

I remember training a 55-year-old powerlifter who could handle high-intensity (RPE 8-9) work just fine but needed substantially more recovery time between sessions. We modified his program to include just 1-2 high-RPE sessions per week, with the remaining work at RPE 6-7. This approach maintained his strength while accommodating the slower recovery typical of masters athletes. For most older lifters, I’ve found that limiting exposure to RPE 9+ work and emphasizing volume at moderate RPE (7-8) produces the best long-term results.

Youth athletes present a completely different challenge. When I started coaching high school weightlifters, I quickly realized that teenagers often have no concept of regulating effort! Their natural enthusiasm leads to every set being RPE 9-10, which is a recipe for burnout. For young athletes, I’ve found success with very strict RPE caps (nothing above 8 for most training) and extensive education about the importance of submaximal work. This approach teaches sustainable training habits while allowing for appropriate development.

The beginner versus advanced lifter distinction is crucial for RPE implementation. With beginners, I start with a simplified RPE framework – often just “easy,” “medium,” and “hard” rather than the full 1-10 scale. As they develop better body awareness, we gradually transition to the complete RPE system. Advanced lifters, in contrast, can often distinguish between RPE 8 and 8.5 with remarkable precision, allowing for much more nuanced programming.

Injury management using RPE has been one of the most valuable applications in my coaching. When working with a client recovering from a shoulder injury, we used RPE as a pain management tool – keeping all pressing movements below RPE 7 and using pain as an additional feedback mechanism. The beauty of this approach is that it automatically accounts for good and bad days in the recovery process, something percentage-based loading simply cannot do.

Female athletes often experience significant strength fluctuations throughout their menstrual cycle, making RPE particularly valuable. I coach several competitive powerlifters who report RPE increases of 1-1.5 points on identical loads during certain phases of their cycle. Rather than fighting this physiological reality, we embrace it – adjusting training emphasis based on how they’re feeling and saving the highest intensity work for phases when perceived effort is lowest.

I’ve had the privilege of working with several adaptive athletes, including a Paralympic powerlifter. RPE was absolutely essential in this context because standard percentage-based approaches simply don’t account for the unique considerations of adaptive athletes. We developed a modified RPE scale that incorporated not just proximity to failure but also technical execution and pain/discomfort levels, creating a more holistic approach to training intensity.

Future Trends in RPE-Based Program Design

The future of RPE training looks incredibly exciting! I’ve been testing some cutting-edge approaches that I believe will become mainstream by 2025, and the potential for even more personalized training is mind-blowing.

AI and machine learning applications for RPE prediction represent the next frontier. I’ve been beta-testing a system that uses previous training data to predict how a given session will feel based on recovery metrics, recent training history, and external stressors. Last month, it accurately predicted that my planned squat session would feel about 1 RPE point harder than normal due to poor sleep quality the previous two nights. The system suggested a 10% load reduction to achieve the target RPE, and it was spot-on! While this technology is still developing, I expect it to become much more accessible and accurate in the next few years.

Wearable technology integration with subjective RPE scores is another area seeing rapid advancement. I’ve experimented with systems that combine heart rate variability, sleep quality metrics, and subjective wellness scores to create “RPE modifiers” for daily training. For example, if your recovery metrics are significantly below baseline, the system might suggest reducing target loads by 5-10% to achieve the planned RPE. The correlation between these metrics and actual performance isn’t perfect yet, but it’s improving quickly.

The research on RPE reliability and validity continues to evolve in fascinating ways. Recent studies have shown that with proper training, lifters can become remarkably consistent in their RPE ratings, with test-retest reliability approaching that of objective measures like velocity. I’ve noticed this in my own practice – clients who initially showed wide variability in their RPE assessments develop much more consistent ratings after 3-4 months of guided practice. This improving reliability makes RPE an increasingly valuable tool for both research and practical application.

Personalized RPE scales based on individual response patterns might be the most exciting development I’m seeing. Traditional RPE scales assume a relatively linear relationship between RPE and proximity to failure, but this relationship varies between individuals! I’m working with several clients using modified RPE scales that account for their unique response patterns. For “grinders” who can maintain force production even as they approach failure, we use a compressed scale for the higher ranges. For “speed-sensitive” lifters who show earlier velocity drops, we expand the upper range of the scale.

The integration of RPE with biofeedback systems is becoming increasingly sophisticated. New technologies allow for real-time feedback on bar speed, force production, and even technique metrics alongside subjective RPE ratings. This concurrent feedback helps lifters calibrate their perceptions more accurately. I was skeptical about this approach until trying a system that displayed my bar velocity immediately after a set, allowing me to compare my perceived RPE with objective performance metrics. After just a few weeks of this feedback, my RPE accuracy improved dramatically.

Remote coaching platforms are rapidly evolving to incorporate RPE in more sophisticated ways. The systems I’m using now allow clients to report not just an RPE number but also qualitative feedback – bar speed, technical execution, and subjective feelings. This richer data helps me make better programming decisions even without being physically present for the session. As video analysis capabilities improve, I expect these remote RPE assessments to become even more accurate and useful for distance coaching relationships.

Conclusion

Understanding and implementing RPE in your strength program design is no longer optional—it’s essential for creating truly effective and personalized training approaches. I’ve seen firsthand how this simple but powerful tool can transform training outcomes for everyone from beginners to elite athletes.

When I think back to my rigid, percentage-based programs from years ago, I can’t help but cringe a little! The difference in both results and enjoyment has been night and day since adopting RPE methods. My clients report feeling more engaged with their training, more in tune with their bodies, and more confident in their ability to regulate effort appropriately.

By combining objective measures with this powerful subjective tool, you can create programs that adapt to your body’s daily readiness while ensuring consistent progress. I’ve found that the sweet spot lies in using RPE as your primary intensity guide while still maintaining objective performance metrics as a reality check. This combined approach provides the flexibility of autoregulation with the accountability of measurable progress.

Remember that RPE mastery takes practice, but the investment in learning this skill pays tremendous dividends in training efficiency and results. Don’t get discouraged if your initial RPE assessments feel inconsistent or inaccurate – this is completely normal! Most lifters need 2-3 months of regular practice before developing reliable RPE sensitivity. Stick with it, use video feedback when possible, and gradually you’ll develop the perceptual accuracy needed for effective autoregulation.

Whether you’re a coach or an athlete, I encourage you to start incorporating RPE methodologies into your training immediately. Start simple – perhaps just rating your working sets after completion to develop your RPE sensitivity without using it to guide loading decisions yet. As your perceptual accuracy improves, you can begin implementing RPE targets to guide training intensity, eventually developing a fully autoregulated approach.

What RPE-based approach will you try in your next training session? Will you start with post-set ratings to develop your perceptual accuracy, or dive right into RPE-guided loading? Perhaps you’ll experiment with daily undulation based on RPE targets rather than fixed percentages? Share your experiences in the comments below – I’d love to hear how RPE transforms your training approach!